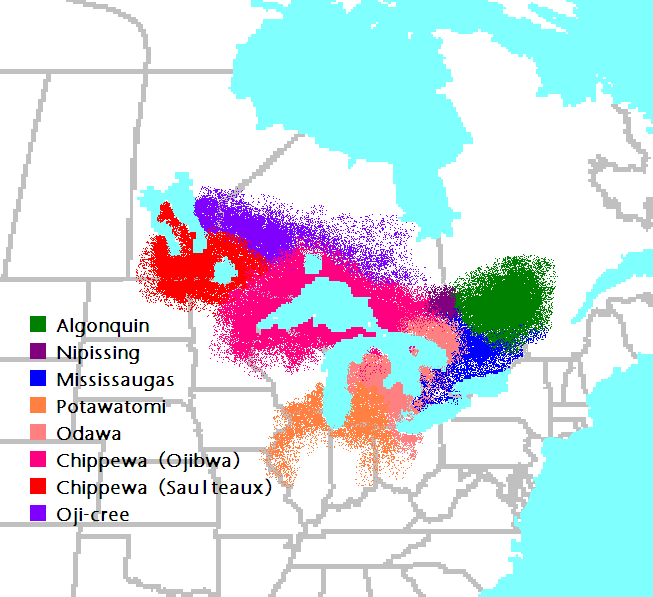

According to oral traditions, the Ojibwe, part of the Algonquian languages-speaking peoples, coalesced on the Atlantic coast of North America. About 500 years ago, the ancestors of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe began migrating west. This tradition has been confirmed by linguistic and archeological evidence.

The effects of colonization and assimilation have taken their toll on the number of native language speakers and socioeconomic conditions have not made the task of retaining languages any easier. As time goes on, revitalization efforts of any size will become increasingly difficult. Today, native languages and cultures are at a critical point in their existence due to the number of Elders and language speakers that have died as a result of the COVID-19 virus.

The Ojibwe language is spoken in a series of dialects occupying adjacent territories, forming a mutually intelligible language between them. The Mille Lacs sound includes speakers from different communities with variations of the Southwestern Ojibwe Dialect.

Amik (Larry Smallwood) stated, “Namanj igo ge-inwegwen a’aw waa-nitaa-ojibwemod, booch igo da-nisidotaagod iniw manidoon.” – Whatever dialect you learn or however you learn to speak Ojibwe, the creator will always understand you, no matter how you sound. There is no single dialect that is considered the most prestigious or most prominent. Typically, second language learners from many Ojibwe communities study multiple dialects to exercise their capability of understanding Ojibwe and building their fluency.

The Mille Lacs Dialect of Ojibwe is considered an endangered language. In 2019, approximately 25 elders were identified as fluent speakers at Mille Lacs. Today, that number has decreased to approximately 19. Four fluent speakers passed away just this year. There are very few Ojibwe speakers left. Ojibwe language in Minnesota is listed as “severely endangered.” (UNESCO, 2010). Today Ojibwe is mainly spoken by elders over the age of 70. Even when not considering the continuing pandemic – COVID-19 disproportionality affects Indigenous communities, as well as the elderly – the number of first language speakers is expected to decline significantly in the next five years.

As part of its effort to assimilate American Indians into mainstream society, the federal government launched an assault on Native languages. For example, in the 1890s the government built twenty-five off-reservation boarding schools to which many Indian children were forcibly removed and where they were prevented from speaking their Native languages.

The result of this decades-long policy was a devastating loss of Native languages. Many tribes struggled to preserve their languages even as the number of fluent speakers dwindled. Among these tribes was the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe.

By the 1990s, Native language use among the Mille Lacs Band had clearly declined while estimates indicated that, by 1994, only ten percent of Mille Lacs Band members could speak the Ojibwe language fluently. The youngest Native speaker was thirty-seven years old. Mille Lacs leaders, educators, and citizens feared that the loss of the Ojibwe language would bring about the demise of tribal traditions and Ojibwe identity among their band members.

To avert this crisis, the faculty of the Nay Ah Shing School, a school owned and operated by the Mille Lacs Band, formed an Elders Advisory Board comprised of five traditionalists for the purpose of establishing an intensive Ojibwe language and culture program. Their hope was that this program would foster the Mille Lacs Band members’ fluency and pride in using the Ojibwe language. They believed that restoring the Band’s language would foster a long-term process of cultural renaissance and lay the foundation for stronger self-governance.

The language crisis in Native communities is so widespread that the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) has drafted a resolution that will be voted on at its upcoming convention “Declaring Native American Languages in a State of Emergency and Support for an Executive Order on Native American Language Revitalization”. The resolution states, “NCAI acknowledges that Native Languages are in a State of Emergency, for the first time in the long history of Indian Nations the vast majority of the 574 federally recognized tribes no longer have active language communities. All existing Native Languages need immediate support at the local tribal , state, and national levels”. The resolution calls upon President Biden to pass an Executive Order promising to promote tribal language and culture in education systems impacting Native learners.

Native languages are more than just words, as cultural values, tribal customs, and ceremony are embedded in them (Mmari, Blum, Teufel-Shone, 2010). Additionally, Indigenous languages serve as protective factors for Indigenous communities. Studies demonstrate that “people who speak their Native language(s) have enhanced mental health and happiness.” (Hallett, Chandler, & Lalonde, 2007; Ball & Moselle, 2013; Dockery, 2011). At Mille Lacs, we know that gaining knowledge of our Ojibwe language and culture as well as participation in cultural activities has played a significant role in contributing to the healing of our people.

Please note, there are audios that are password protected for the purpose of cultural sensitivity. These are not located on this page however are available for those who use the contact tab. In addition, due to elder request they have asked that certain sections of audio only be listened to/learned from those who identify as said gender throughout their daily life. Miigwech.

To learn more, view our language resources:

Waabooyaanike – Quilting

October 10, 2023/by Karen PDewe’igan – Big Drum

October 10, 2023/by Karen PElder Archive Recordings: Melvin Eagle

May 19, 2023/by James ClarkProtected: Protected: Elder Archive Recordings, Larry Smallwood

March 17, 2023Elder Archive Recording: Ole Nickaboine

January 9, 2023/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Albert Churchill

January 9, 2023/by James ClarkThe Woodlands: The Story of the Mille Lacs Ojibwe

December 28, 2022/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Lee Staples

October 6, 2022/by James ClarkElders Ojibwe Language Conference 2006

July 5, 2022/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Shirley Boyd

December 30, 2021/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Bette Sam

December 30, 2021/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: James Clark

December 28, 2021/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Julie Shingobe

December 28, 2021/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Mille Benjamin

December 28, 2021/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Larry Smallwood

December 28, 2021/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Raining Boyd

December 28, 2021/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: James Mitchell

December 28, 2021/by James ClarkElder Archive Recordings: Elfreda Sam

December 28, 2021/by James ClarkAanjibimaadizing

This website was created by the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe Aanjibimaadizing Program to preserve, protect, and share the history of their people, culture, traditions and language.

To learn more about Aanjibimaadizing and the services it offers, visit https://aanji.org/